Let me be clear: This column is not predicting that Democrats will lose control of the Senate and/or the House in next year’s midterm elections. But I am about to argue that if Democrats lose one or both chambers, they will look back on some of their decisions and actions in these first few months of this administration and Congress with a great deal of regret.

There is an established pattern of parties convincing themselves they have a mandate when in fact they don’t, and Democrats seem to be keeping to it. Indeed, if there was a mandate, it was for a president who would talk and act differently from President Trump, but not for much else. After expectations of strong gains in the House and Senate last year, Democrats just barely held the House and won the Senate by the narrowest possible margin.

In fact, it appears that a narrow but, in retrospect, critical slice of voters who looked to be headed in an anti-Republican direction got cold feet amid charges that Democrats were pushing a socialist agenda—specifically that they wanted to “defund the police,” “abolish ICE,” and impose single-payer health insurance. Never mind that Joe Biden and most mainstream Democrats embraced none of those views. It seemed to be enough of a concern that more than a few voters peeled off and stuck with the GOP.

As this column has repeatedly argued, the decision to push this relief package through on a party-line vote via the budget-reconciliation process (to say nothing of talk that they may do the same with infrastructure and immigration) seems a bit incongruous with the soaring rhetoric of Biden’s inaugural address.

Despite the bitter—and avoidable—partisanship, Biden’s coronavirus package will loom large next year. Today the package is extremely popular, with approval ratings of between 60 and 70 percent. Of course, giving voters money and other benefits will always be popular, but remember that the 2017 tax cuts authored by Trump and the Republicans weren’t a big hit at the time with voters, who eventually gave the Democrats control of the House in the following 2018 midterm election.

But with 596 days before Election Day 2022, it remains to be seen which party will do a better job of framing the choices around the American Rescue Act, and what its economic impact will be. To the extent that the ARA is widely perceived as an effective response to the pandemic, giving the economy a needed shot in the arm, it will remain a plus. But if it is seen as simply a big spending program or worse, overheats the economy and causes a significant rise in inflation, that would be a big problem for Democrats.

On the economic side, there is a fierce debate going on about the size of the package between two Democratic economists: New York Times columnist Paul Krugman argues that it is both right-sized and necessary, while former Treasury secretary and Harvard economics professor Larry Summers worries that it’s too big and risky.

The reality is that the ARA is a very big and far-reaching piece of legislation that did provide ample funding for vaccines and testing but also drew heavily from the Democratic wish book of the last couple of decades. Some even opined approvingly that the law was akin to the moves that President Franklin Roosevelt and the Democratic Congress enacted in 1933 addressing the Great Depression. Biden himself quoted Sen. Bernie Sanders’s endorsement of the package as “the most progressive bill he’s ever seen passed since he’s been here.”

Back to the midterm elections: While there are independents who vote in every general election, the proportion of independents voting in midterms is lower than in presidential-election years. Midterms are more a contest over which side’s base is more motivated—or, to put it another way, which party has more drop-off from the presidential election two years earlier.

It should be noted that whether there is a GOP civil war between the Trump and Not-so-Trump sides will obviously be relevant.

Unique to 2022 is that the preceding midterm and presidential elections had record-high voter participation. 2018 featured the highest midterm turnout since 1914; 2020, the largest presidential turnout since 1900. Of course, the trigger for both record turnouts was the incumbent president: Both Trump-lovers and Trump-loathers came out of the woodwork, raising an interesting question of which of those two groups is more likely to drop off in 2022, when he’s no longer commanding the bully pulpit.

Soon after Biden won last November, I wondered how Republicans could keep their base stirred up with a Democratic president who didn’t seem likely to be as polarizing, at least to the GOP and conservatives, as Presidents Clinton and Obama were. Still, while the administration is far from radical or socialist, it is far more progressive than many expected when Biden secured the nomination a year ago.

Talk that House Democrats could seek to overturn the state-certified results in Iowa’s 2nd Congressional District, a bit of a flip-flop from recent arguments over the 2020 election results, reminds some old-timers of a similar move in 1984. Then, a Democratic majority overturned the results in Indiana’s 8th Congressional District, a move that incensed the GOP and was a major contributing factor in Newt Gingrich’s eventual takeover of House Republican leadership, effectively pushing aside Minority Leader Bob Michel and the establishment.

Whether or not Democrats go through with it this time, Republicans are getting more than enough ammunition to rile up their base. Remember, hate and fear are the two strongest motivating factors in politics, far more than love or appreciation. In fact, midterm-election voters are much more likely to punish a president or majority party over disagreements or disappointments than to reward a job well done.

Subscribe Today

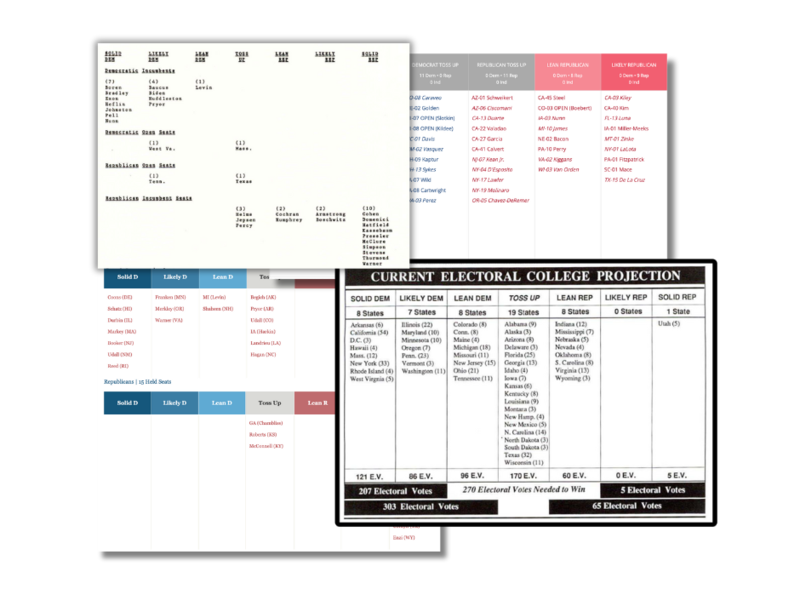

Our subscribers have first access to individual race pages for each House, Senate and Governors race, which will include race ratings (each race is rated on a seven-point scale) and a narrative analysis pertaining to that race.