In the military, an enlisted person impersonating an officer is a very serious offense. In politics, a party pretending and acting as if it has a mandate is a similarly serious transgression.

Mandates are the product of landslide victories, a margin of 10 percentage points or more in presidential politics. There have been four such landslide wins in the post-World War II era. Presidents Lyndon Johnson and Nixon both recorded 23-point victories—the former in 1964 over Barry Goldwater, racking up 486 out of 538 Electoral College votes, the latter in 1972 over George McGovern, garnering 520 electoral votes. Ronald Reagan was responsible for the other two—an 18-point win over Walter Mondale in 1984, garnering 525 electoral votes, and by 10 points and with 489 electoral votes in 1980, en route to defeating President Carter. In terms of congressional politics, let’s just say that mandates come with massive majorities.

Presidential landslides like those are now all but impossible. Roughly 45 percent of voters nationwide now identify as Democrats or are independents who reliably vote that way, with roughly the same proportions for Republicans. It no longer matters how awful someone’s own party nominee is, or how great the other side’s is. Voters stick with their party in virtually a parliamentary fashion. This dynamic effectively constructs high floors under each party, but low ceilings. The determining factors become which party’s voters have a higher level of enthusiasm and intensity, and in which direction the uncommitted 10 percent of the electorate breaks.

Another change since the 1980s is the passion and conviction within each party, a projection of righteousness that does not tolerate any contrary point of view. This has created a situation in which no win is too small to claim a mandate to do transformational things. We saw this with Republicans in 2017 and 2018 after Donald Trump added the presidency to the GOP’s existing House and Senate majorities, despite losing the popular vote to Hillary Clinton by 2.1 percentage points.

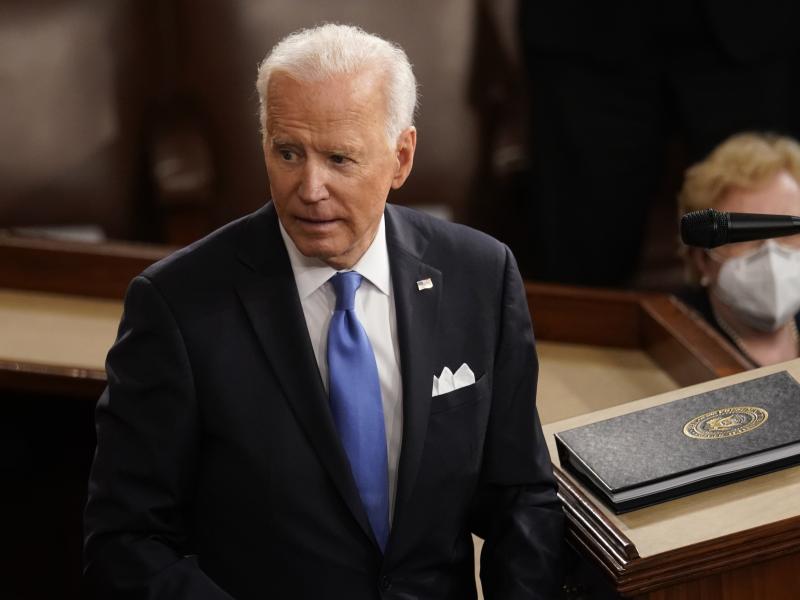

Democrats also earned a trifecta in the 2020 cycle, but President Biden’s win rested on a mere 126,000 votes spread across Georgia, Arizona, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania. The Democratic majority in the Senate was a product of Jon Ossoff’s 55,000-vote win over David Perdue in Georgia. In the House, the margin was about 32,000 combined votes scattered over five congressional districts.

Why did Biden win the Democratic nomination? Because he was not Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren. Much of the party went into panic mode when it appeared that Sanders would win the nomination, and they put aside their reservations about Biden. Why did Biden win the general election? The answer is shorter. Because he was not Donald Trump.

A month before the 2020 election, it sure looked like Democrats were headed for a big win, with considerable talk about a blue wave. Yet perhaps after hearing all the talk of about democratic socialism, Medicare-for-all, and the Green New Deal, some reconsidered their support for Democrats for the House and Senate and changed their intentions.

In other words: These were not landslides, and this was no mandate for fundamental change. The message that voters sent was a different one than what many Democrats on Capitol Hill appear to have heard, inclined as they are to remake the U.S. economy and the social safety net via a $3.5 trillion reconciliation measure.

Midterm elections turn on whether voters want to stay the course or feel it’s time for a change. Are they satisfied with what is happening or not? Do they feel like a new leader is on top of the job or not?

But they’re also about intensity. Ask yourself this question: Which party is more likely to turn out in big numbers, the members of a party that in the most recent election got what they wanted, or those of a party that had it taken away from them? Or worse, feel it was stolen from them?

This article was published for the National Journal on September 21, 2021.

Subscribe Today

Our subscribers have first access to individual race pages for each House, Senate and Governors race, which will include race ratings (each race is rated on a seven-point scale) and a narrative analysis pertaining to that race.