[This article was originally published on February 27, 2020 at the New York Times]

It’s no secret that Democratic primary voters prize fall “electability.” But for all the clamor about progressive versus moderate choices, the obstacles to pulling voters toward Democrats particularly in the battleground states could prove more cultural than ideological.

Last summer, Senator Elizabeth Warren electrified huge crowds at rallies in Seattle, Austin and New York. The events had one thing in common besides her populist pitch for “big structural change.” At each stop, her trademark selfie lines were less than a mile from a Whole Foods Market, a Lululemon Athletica and an Urban Outfitters.

These high-end retailers and brands, popular with urban millennials and affluent suburbanites alike, are increasingly correlated with which neighborhoods are trending blue. The drawback for Democrats? Just 34 percent of U.S. voters — and only 29 percent of battleground state voters — live within five miles of at least one such upmarket retailer, and the Democrats’ brand is stagnant or in decline everywhere else.

Once dominant in labor halls, Democrats are more ascendant than ever near galleria malls. But the reality for Democrats is if they aren’t able to stop their slide in less elite locales, President Trump’s advantage in the Electoral College could further widen relative to the popular vote.

In fairness, Ms. Warren and the other top 2020 contenders are spending more of their time and energy seeking to woo voters in less cosmopolitan settings. They have no choice: Sixty-nine percent of U.S. voters live closer to a Cracker Barrel, Tractor Supply Company, Hobby Lobby or Bass Pro Shops location than to one of those high-end brands.

But it wasn’t always this hard for Democrats. In the 1990s, millions of less religious middle-class heartland voters opted for Democrats, in part because they viewed Republicans as the party of rich people and “Bible thumpers” who wanted to impose their moral values on the country. Today, many of those same voters might feel they have even less in common with liberal arts graduates in trendy ZIP codes willing to pay $14 for a half liter of avocado oil, $59 for a recycled tie-dye sweatshirt, $158 for yoga tights or $1,449 for a smartphone.

In many ways, what people buy, eat and wear is just another lens through which to view the growing political divide between Americans with college degrees and those without.

“It’s cultural arrogance,” said the veteran Democratic strategist James Carville, who now teaches at Louisiana State University. “On taxing the rich, health care, Roe v. Wade,” he added, “we’re in the majority on all these issues. But in this country, culture trumps policy. The urbanists — voters think they’re too cool for school. And voters pick it up.”

His advice to today’s Democrats: “If you want to win back loggers in northern Wisconsin, stop talking about pronouns and start talking more about corruption in Big Pharma.”

Plenty of different factors decide vote choices, race and religion among them. There used to be far more high-income white Republicans than high-income white Democrats; today their numbers are roughly even. But the biggest swing among voters in recent years — in parts of Europe, too — is happening among whites along educational lines.

This cultural and class disconnect was one of the reasons Mr. Trump’s 2016 victory blindsided so many academics, pundits and journalists. He was unpopular relative to past G.O.P. nominees in the wealthy, white and highly college-educated neighborhoods — the Whole Foods bubbles — where such people tend to live and work.

The upmarket bubble

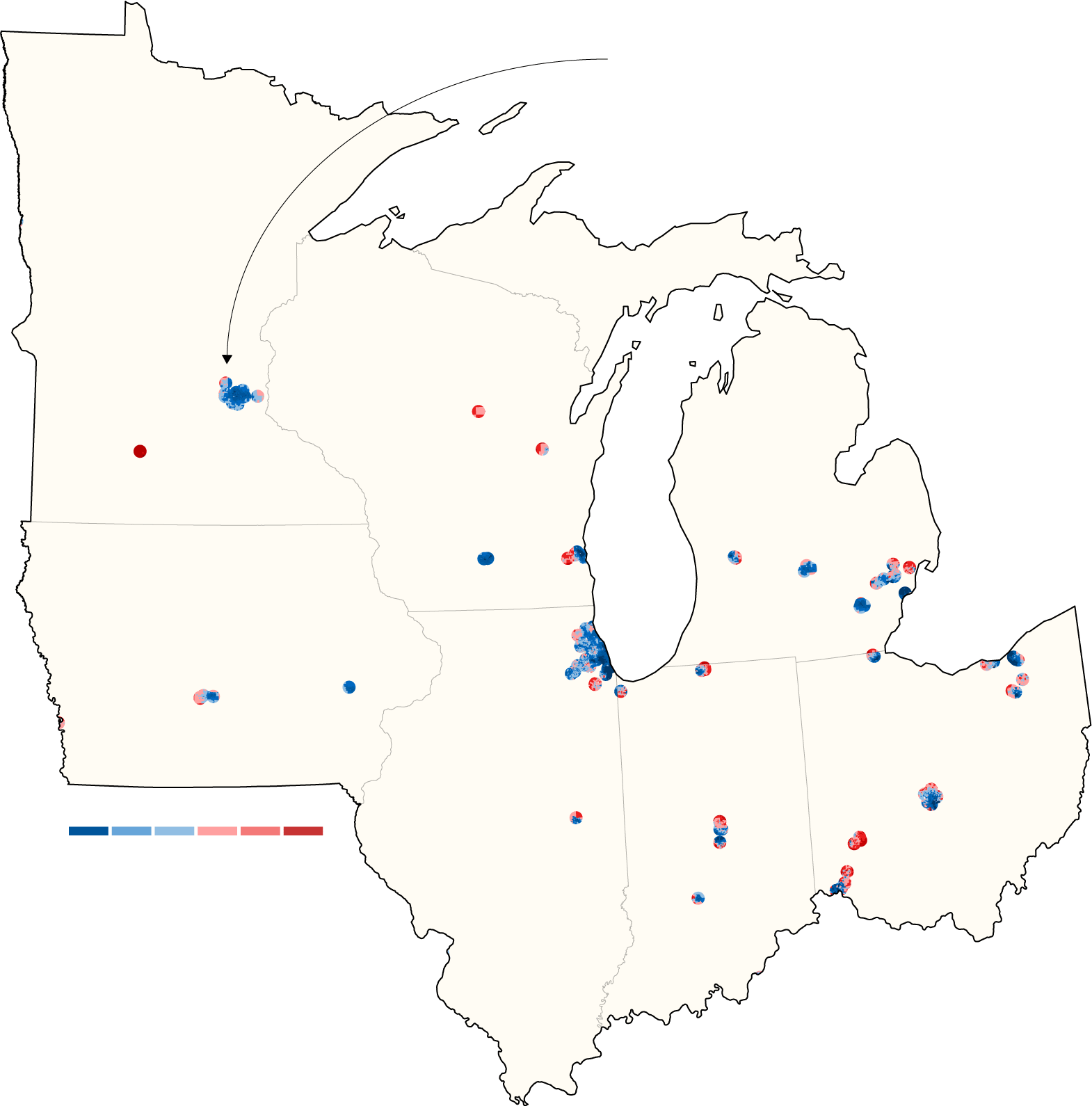

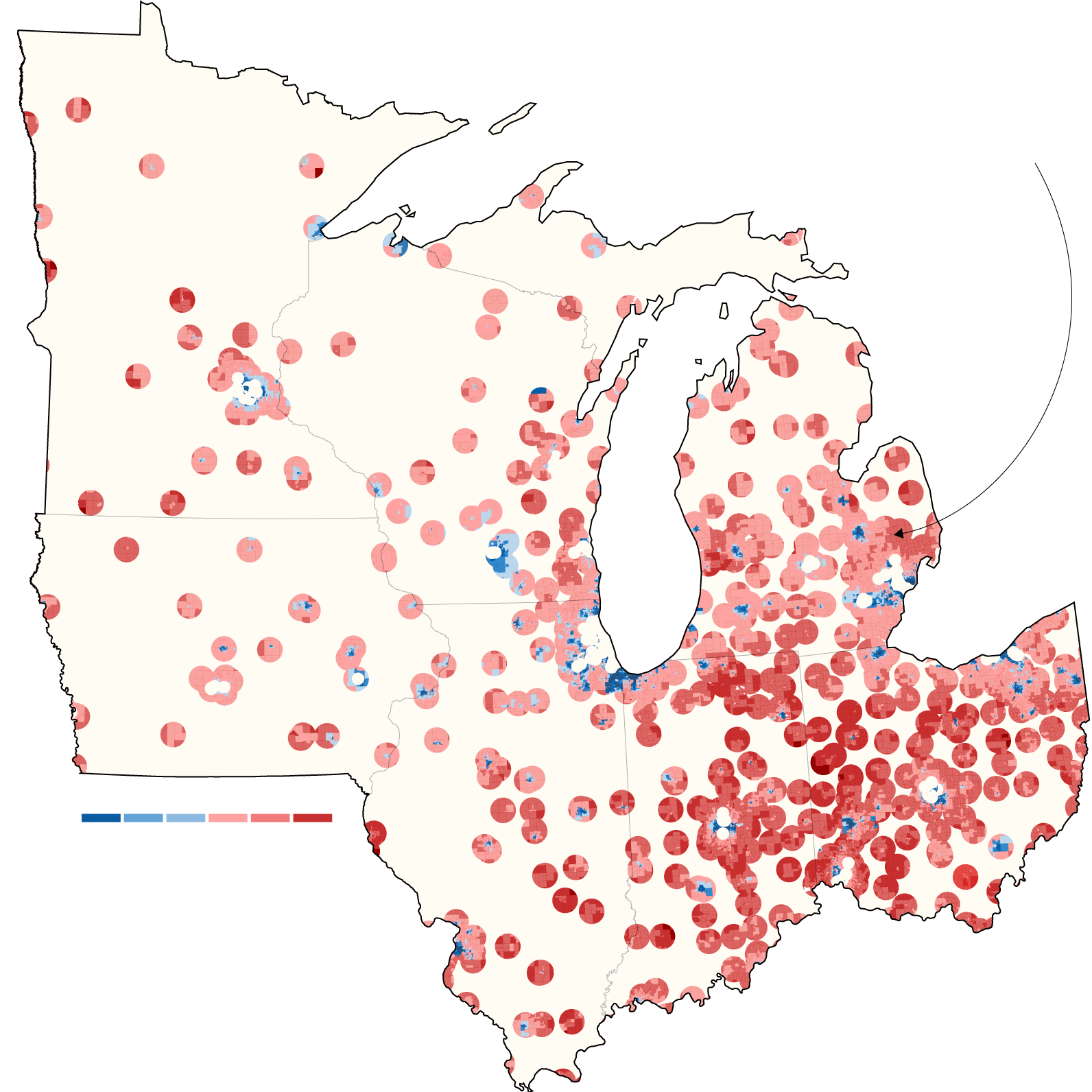

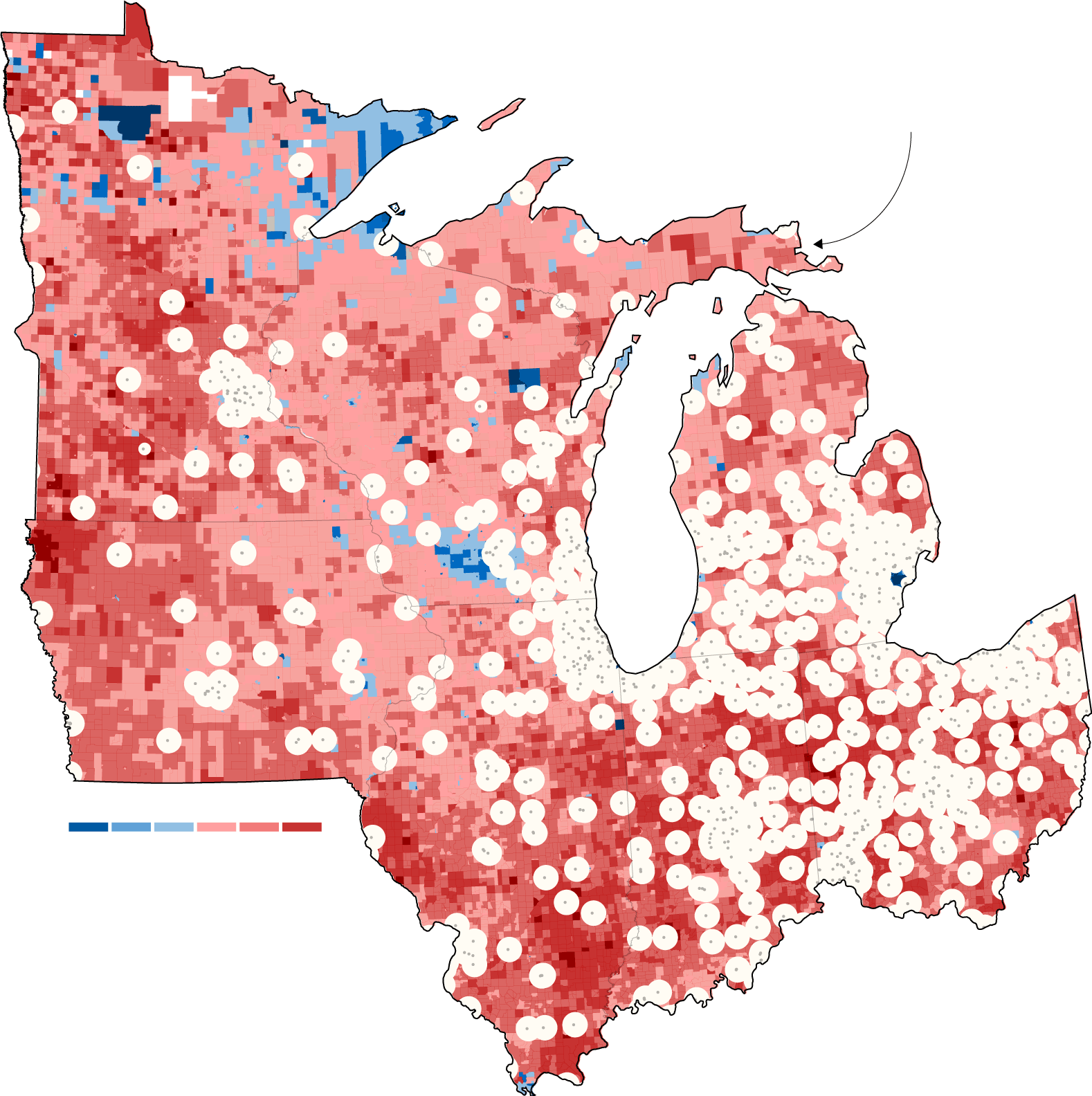

To quantify the relationship between retail locations and voting, we analyzed retail and precinct-level election data compiled for this article by the U.C.L.A. postdoctoral research fellow Ryne Rohla and Grant Gregory, a pollster for Breakthrough Campaigns.

After examining the voting patterns surrounding over 100 popular American chains, we zeroed in on eight national brands — each with retail locations in over 40 states — that proved useful predictors.

Of the eight brands, the four correlated with Democratic vote growth were the Amazon-owned organic mecca Whole Foods Market; the Canadian-based yoga and “athleisure” apparel retailer Lululemon Athletica; the hipster fashion magnet Urban Outfitters; and the glassy, minimalist Apple Store. Let’s call these “upmarket” brands.

The four brands correlated with recent Republican gains were the Southern-themed Cracker Barrel Old Country Store; the booming rural lifestyle chain Tractor Supply Company; the arts-and-crafts giant Hobby Lobby; and the outdoor recreation hub Bass Pro Shops. We’ll call these “down-home” brands.

Next, we divided the country’s electorate — based on the proximity of these stores to the geometric centers of America’s more than 169,000 voting precincts — into three groups:

Upmarket bubbles: voters living less than five miles from a current Whole Foods, Lululemon, Apple Store or Urban Outfitters location (34 percent of the electorate in 2016).

Down-home zones: voters living less than 10 miles from a current Cracker Barrel, Tractor Supply, Bass Pro Shop or Hobby Lobby location (these stores tend to be in less densely populated areas) — but more than five miles from the nearest “upmarket” retail location (50 percent of the electorate in 2016).

Chain-sparse communities: voters who don’t live close enough to any of these retail stores to fall into either category (16 percent of the electorate in 2016).

The good news for Democrats: Over the past few election cycles, they’ve gained a lot of ground among voters in upmarket bubbles. In 2016, Hillary Clinton carried them by 31 percentage points, up from Barack Obama’s 26-point margin in 2012. And among the 4 percent of voters within one mile of a current Whole FoodsLululemonUrban Outfitters/Apple Store location, Mrs. Clinton won by 45 points, up from Mr. Obama’s 36-point margin in 2012.

How These Categories Break Down Nationally*

This retail realignment was also on display in the 2018 midterms: Of the 43 districts Democrats wrested from G.O.P. control to take back the House, 65 percent contained a Whole Foods Market, compared with 38 percent of all districts that elected a Republican. And both states where Senate Democrats scored gains — Arizona and Nevada — have upmarket numbers above the national average.

But the challenge for Democrats is that relatively few voters, especially in Electoral College battleground states, live in these upmarket bubbles.

Consider that in the most recent presidential election, 53 percent of all California voters and 57 percent of all Massachusetts voters lived within five miles of a current Whole Foods, Lululemon, Urban Outfitters or Apple Store location. But in electoral battlegrounds, just 33 percent of voters in Florida, 32 percent in Pennsylvania, 24 percent in North Carolina, 20 percent in Wisconsin and 19 percent in Michigan did.

In 2016, among the roughly half of U.S. voters who live in down-home zones — think of places like Saginaw, Mich.; Erie, Pa.; or Green Bay, Wis. — Mrs. Clinton lost by 10 points, worse than Mr. Obama’s six-point loss in 2012 and his two-point loss in 2008. And among the 16 percent of voters who don’t live particularly close to one of these retail brands at all, she lost by 22 points, far worse than Mr. Obama’s 11-point loss in 2012 and his six-point loss in 2008.

And all three House districts and all four states — Florida, Indiana, Missouri and North Dakota — where Republicans gained House or Senate seats from Democrats in 2018 feature either down-home or chain-sparse shares well above the national average.

What’s more, the below-average upmarket shares in Minnesota (30 percent), New Hampshire (22 percent) and Maine (11 percent) suggest Mr. Trump might even have some cultural upside in a few states Mrs. Clinton narrowly carried.

If residential patterns around retail are electoral destiny, trends suggest the Democrats’ future lies in the Southwest and Sun Belt. Of the six states Mr. Trump carried by less than four points in 2016, Arizona stands out for an upmarket share (37 percent) higher than the nation’s — a good sign for Democrats in that increasingly metropolitan, diverse state.

Democrats might also be encouraged that Texas’ upmarket share (33 percent) is also higher than those of many other traditional battlegrounds. But President Trump’s 2016 margin of victory in Texas was nine points — still a lot of ground for the 2020 Democratic nominee to make up.

Bridging a cultural divide

There will always be plenty of voters who defy stereotypes: Republicans who shop at Whole Foods and Lululemon, or Democrats who stop at Cracker Barrel on road trips. But much as retail chains have effectively micro-segmented consumers to map where new locations will perform best — as Whole Foods has done around clusters of college graduates — candidates and parties can increasingly depend on “lifestyle brand” data to predict voter behavior.

Perhaps no presidential candidate has flaunted wealth to the degree Mr. Trump has. But from construction sites to Howard Stern call-ins to WWE appearances, he also spent decades before becoming a politician developing a blue-collar persona. In 2016, as the G.O.P. nominee, he defied history by winning a higher share of low-income whites than high-income whites. And the deepening fault lines of elite versus anti-elite could help Mr. Trump once again this November — no matter the Democratic nominee’s ideological orientation.

Many Democrats who succeeded in 2018 — such as the Marine veteran Conor Lamb in a Pennsylvania House race, the water rights lawyer Xochitl Torres Small in a New Mexico House race and Senator Sherrod Brown, a longtime opponent of job outsourcing, in his re-election in Ohio — had profiles that appealed across this chasm. But it remains to be seen whether the Democratic presidential nominee will be someone whose background and message can bridge the gap.

Most Americans have already chosen sides for the November election, and it’s easy to believe there isn’t all that much sorting left to do. It’s also easy to view the divide as purely urban versus rural. But something all eight of the retailers in this article have in common is a growing presence in the suburbs. That should serve as a reminder that when it comes to elections, not all suburbs look or behave alike .

To beat Mr. Trump, Democrats will probably need a nominee who can relate to people in the modest suburbs of Harrisburg, Pa.; Eau Claire, Wis.; and Fayetteville, N.C. — not just the chic suburbs of San Francisco, Dallas and Washington, D.C.

Subscribe Today

Our subscribers have first access to individual race pages for each House, Senate and Governors race, which will include race ratings (each race is rated on a seven-point scale) and a narrative analysis pertaining to that race.