One of the most immediate repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic on our politics is its impact on who votes and how they do it. Before COVID-19, there was an expectation for record-breaking turnout in 2020. After all, turnout in the 2018 midterm election hit a 100-year high. Plus, polls in 2019 and early 2020 found voters overwhelmingly engaged in the upcoming election. For example, a February Gallup survey found that 59 percent of Americans were enthusiastic about voting in November — 13 points higher than a similar point in 2016 and 12 points higher than early in the 2012 campaign.

Since the outbreak of coronavirus, however, CNN polling has shown a dip in enthusiasm, from 66 percent in early March to 57 percent in early April. Of course, more Americans are worried about paying bills, getting sick, and losing their jobs than they were in early March. As such, an election in November suddenly seems much less relevant. It's also worth noting that enthusiasm to vote is still 16-points higher now than it was in July of 2016 and 9-points higher than it was in March of 2012. However, it's worth watching this "enthusiasm" number closely over these next few months to see which voters say they have become less motivated to participate in the fall election.

At this stage, we also know that voters are uncomfortable about the prospect of showing up to vote at a traditional voting location. An early March survey by Pew Research found two-thirds of Americans worried about showing up to vote in person.

Now imagine a post-Labor Day reality where:

- The virus is still raging, and most of us are still under some form of a shelter at home order.

- We have regional hot spots, but the rest of the country gets back to normal.

- We are more or less 'back to normal,' but the fear of crowded spaces continues.

- Things get better over the summer, but a new wave is predicted to break out in October or November.

The election the other week in Wisconsin gave us a sneak preview of what an election done under uncertain health circumstances could look like. There were mixed messages from political leaders. Confusion. Partisan fighting. Long lines of voters donning masks and gloves, waiting to vote at a limited number of open polling places.

The fact that "1.1 million mail ballots were received in time to be counted—a record for any election in the history of Wisconsin" is impressive and suggests that voters are much more adaptive than we thought possible. But, we also know that many voters were unable to vote because their ballots were never delivered or were sent to wrong addresses. Many voters simply gave up when they saw how daunting the absentee ballot process was. Plus, writes MIT professor Charles Stewart III, "The electorate in a general election is different from the primary election. It's less experienced and has more difficulties at the polls. It will be less capable of jumping through the hoops to get mail ballots, and it will be more reliant on election-day registration to be able to vote in the first place. The municipalities that run elections in Wisconsin will need to double their capacity to handle mail ballots, and ensure that the lion's share of in-person Election Day polling places are staffed. The state has time to plan and execute, but the stakes in November will be higher."

As Stewart notes, states theoretically have the time to prepare for any of the four scenarios I laid out above. But, we also know that partisanship and legislative wrangling is a big—or bigger—hurdle than the ticking clock. For example, the three most important battleground states of the midwest—Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Michigan—all have split control of government, more specifically, Democratic governors and Republican legislatures. The idea that these states could agree upon new laws before November—especially at a time when many state legislatures are trying to avoid meeting in person during this pandemic— seems unlikely.

Instead, what we will have is a hodgepodge of rules and laws, not only by state but in some cases by jurisdiction. In Wisconsin, for example, the city of Milwaukee is planning to send absentee ballot requests to every registered voter in the city. Whether other cities follow suit could have a very significant impact on turnout in the state.

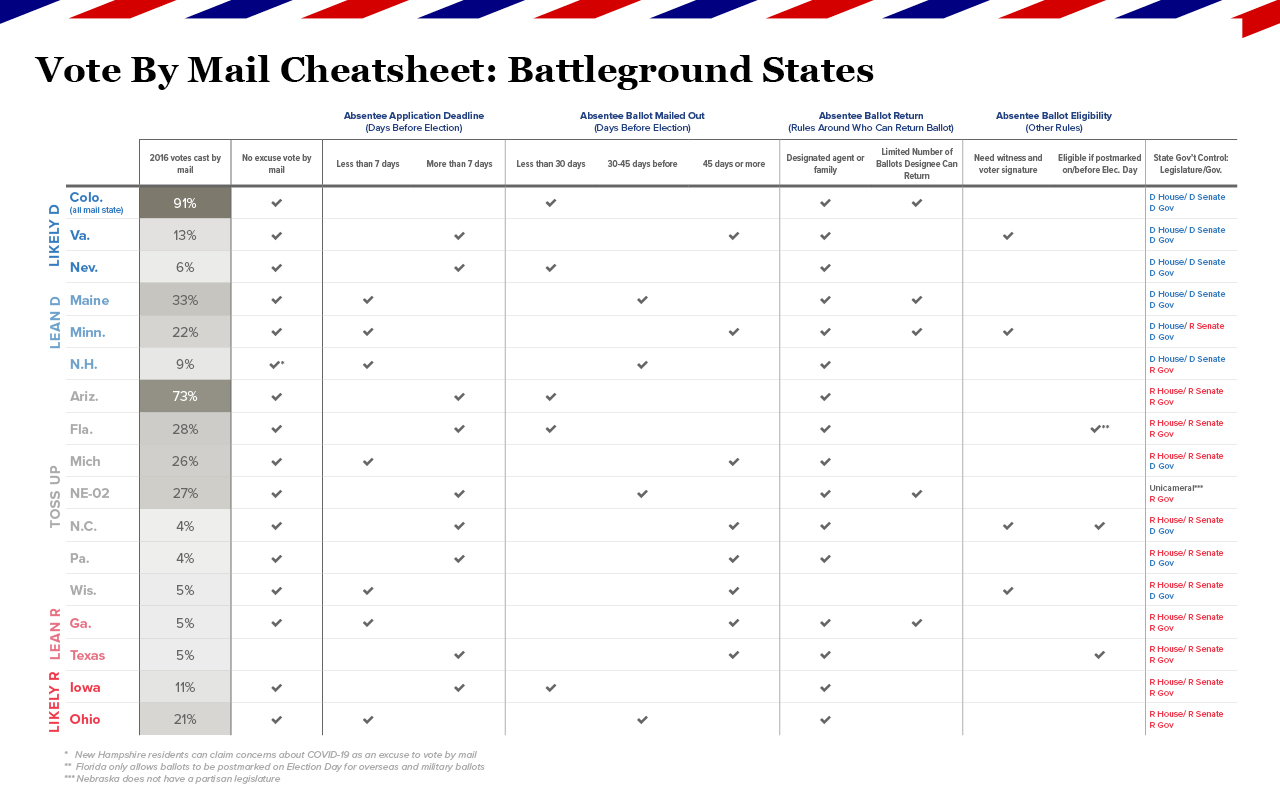

There's no telling where we will be this fall either in the fight against COVID-19 or in the battle over voting access. But, it's helpful to know at least where we begin. To that end, I've put together a chart highlighting what I think are some of the most important vote-by-mail laws in the 17 states that the Cook Political Report rates as the most competitive for the fall election. This information was gleaned from The National Conference of State Legislatures and the Election Assistance Commission.

Here are my takeaways:

- Every battleground state, but for Texas, already allows vote by mail. However, most voters in these states don't use it (except for Colorado, which is a vote-by-mail state). Voters in Arizona are very comfortable with vote-by-mail, as 73 percent cast their ballots this way in 2016. But, in some of the biggest battlegrounds for 2020, including Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and North Carolina, less than 10 percent of voters returned their ballots by mail in 2016. As we saw in the Wisconsin April election, voters can adapt and readjust quickly. But, it is still going to be a lift to convince voters — many of whom are already suspicious of things like machine voting — that sending their ballot in the mail will be safe and reliable. Only eight of these competitive states (Florida, Colorado, Michigan, Iowa, Minnesota, New Hampshire, North Carolina and Virginia), require that the state "track when their ballot has been sent out by election officials and then when the election official receives the marked ballot back, and whether or not the ballot was counted."

- Most states require a ballot to be returned before Election Day. In fact, only two battleground states, Texas and North Carolina, allow for an absentee ballot to be counted if it is postmarked on or before Election Day. Arizona and North Carolina allow a voter to drop off a ballot at any in-person polling place (assuming there will be such things in November). But, the bottom line is that voting by mail takes more planning and forethought than showing up at some point on Election Day at your local voting location.

- Wisconsin has lots of hurdles for voters to get over to receive and return a mail ballot. The Badger State is the only battleground state to require voters to submit ID to receive an absentee ballot, and one of only four of the competitive states to require a witness signature to have that vote counted. These rules were, not surprisingly, a bone of contention this April. Lots of voters complained that they didn't know how to upload a picture of their ID to apply for an absentee ballot electronically. Voters who lived alone worried about exposing themselves to the virus by bringing someone into their homes to sign their ballot envelope. Finally, Wisconsin is one of only 13 states nationally, and the only one of the battleground states, that doesn't address whether a designated agent or family member may return an absentee ballot on behalf of a voter. Think about how close the election in Wisconsin is likely to be. And, now imagine the battles that can and will be fought over each of these rules.

- Vote by mail changes GOTV and spending options and deadlines. Just over half of the battleground states require an absentee ballot to be received at least a week before Election Day. This puts even more pressure on campaigns to find, target and contact their voters as early as possible. It also means redirecting field staff to spend more time than they had originally budgeted to chase absentee ballot applications. In addition, 70 percent of the battleground states send ballots out to registered absentee ballot voters a month to 6 weeks before the election. For voters in a state like Pennsylvania, ballots will start getting to voters in mid-September. For those states that have a history of voting by mail (like California and Arizona), this won't be anything new or unusual. But, for states that don't have a tradition of voting by mail (like Pennsylvania), it will be a big change for voters and campaigns. Moreover, given how quickly this pandemic has wreaked havoc on our health, economy and feelings of safety, just think how different life may look in this country in mid-September or early October than it will in November. It also means that campaigns have to readjust their GOTV schedule. Getting voters to the 'polls' in November may not be as important as making sure that your voters have an absentee ballot in hand and in the postal box by October.

- Preparing for the unknown, "I think that campaigns need to be prepared earlier and be prepared for the unexpected," a top GOP strategist told me the other day. Democratic strategist Jesse Ferguson agrees, telling me via email that when it comes to contacting voters, "targeting too narrowly is always a mistake in an election like this and it's even more so when turnout is as fluid as it may be in 2020. Between new voting reforms, GOP voter suppression and fears of coronavirus, campaigns need to have a wide-angle lens for the voters they have a conversation with." But, those of us who follow, report and analyze elections also have to be prepared to contend with the fact that this election may look different than any we've ever covered. It's one thing to be voting in a time of great change and tumult. It's quite another thing when the act of voting itself may be seen as a risk to one's health and safety. How do you model for that? And, what happens when the rules surrounding vote-by-mail change during the middle of the campaign? Or the courts have to reconcile differences between governors and the legislature (like they did in Wisconsin earlier this month)? In other words, what has already been a crazy and unprecedented election cycle, is going to get even more uncertain.

Subscribe Today

Our subscribers have first access to individual race pages for each House, Senate and Governors race, which will include race ratings (each race is rated on a seven-point scale) and a narrative analysis pertaining to that race.