Why do some social movements become major players in a political party and others don’t? As examples of the latter, in the late 19th century radicals tried to attach themselves to the Republican Party to advance the cause of small farms for former slaves and Populists made anti-Wall Street overutes to the Democrats in the interest of smallholders everywhere. But both major parties were dominated by big business, which wanted hard money, industrial expansion, and cotton grown on large and efficient plantations. As a result radicals and populists simply got pats on their heads.

In the century-plus since then, Daniel Schlozman shows in When Movements Anchor Parties: Electoral Alignments in American History, two other movements actually did break through to become influential “anchors” within the major parties: organized labor for the Democrats starting in the 1930s and, since the late 1970s, white evangelical Christians for the GOP. “No other social movements have built such broad and deep relationships with political parties over such a long stretch of time,” Schlozman argues. Why do social movements seek to embed themselves in a political

Subscribe Today

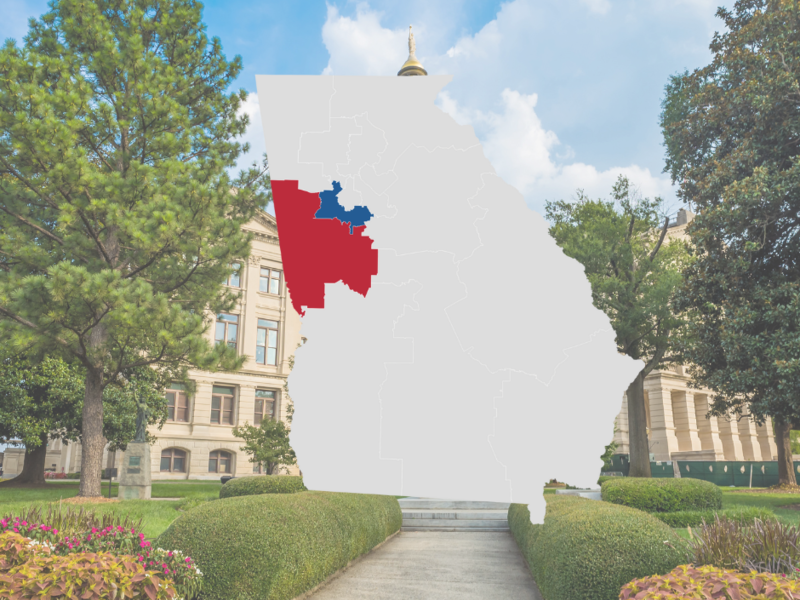

Our subscribers have first access to individual race pages for each House, Senate and Governors race, which will include race ratings (each race is rated on a seven-point scale) and a narrative analysis pertaining to that race.